The following is based on the story of “how” and “why” ARRL’s National Traffic System (NTS) came to be — an expansion of an article by Phil Sager, WB4FDT, and Bud Hippisley, W2RU, originally published in the OOTC newsletter circa 2018.

The Early Years

Back in the days when “spark was king,” Hiram Percy Maxim — a “ham” radio operator in the early 1900s — was unable to send a message from Hartford, CT to Springfield, MA, so he worked a fellow amateur from Windsor Locks, a small town between Hartford and Springfield, and asked him to relay the message to Springfield. This gave Maxim the idea for an organization whose purpose would be to expedite amateur radio traffic handling. Of course, that organization ultimately became ARRL — the American Radio Relay League — and a general mailing initiated by Maxim to promote the League and message handling by amateur radio soon became QST.

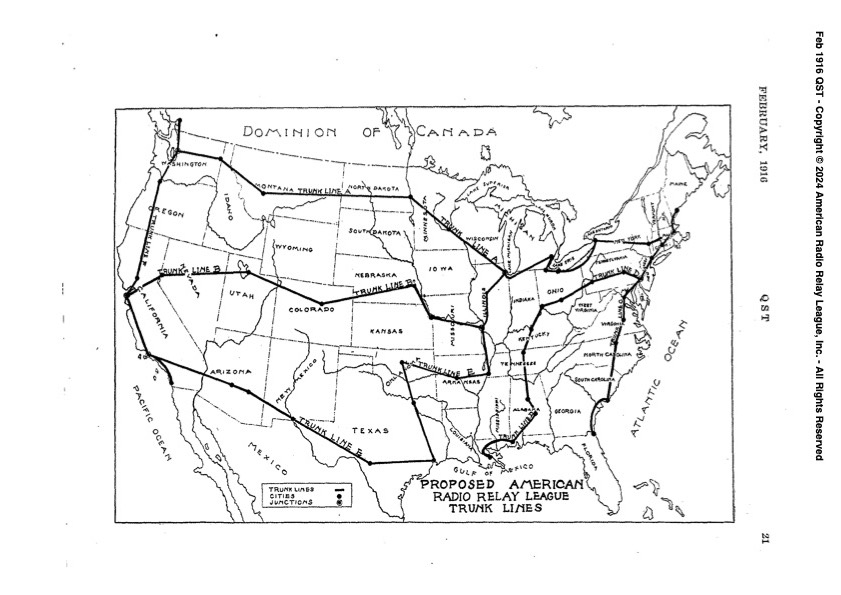

In the February 1916 issue of QST, Maxim outlined his plan for the ARRL to have six trunk lines for passing traffic — three trunk lines running horizontally across the map [of the continental United States] and three running vertically. Within a month, four of the six trunk lines were up and running, and by the end of 1916, more than 150 cities were linked by these trunk lines, with branch lines extending national coverage.

World War I

Following a two-and-a-half-year hiatus caused by World War I, when all of Amateur Radio in the US was shut down, the trunk lines resumed operations in 1919, with rules of traffic handling for ARRL members codified in the February 1920 issue of QST. The official message format was very similar to the current Radiogram format except for a “dynamic” preamble, the contents of which changed with each relay to the next station in the circuit.

The Trunk Line Era (’20s — ’40s)

Beginning in the mid-1920s, as CW began to grow in popularity and more hams gained access to VFOs and multiple crystals, US state or ARRL Section traffic nets — with all their participants on or near each net’s publicized frequency — came into being. When possible, any outgoing traffic was sent to operators who maintained trunk line schedules, and trunk line operators used these new nets to relay incoming traffic to stations close to the message destinations for delivery.

The trunk lines and their local State and Section feeder nets operated continuously until 1941 when WWII forced another shutdown of all Amateur Radio transmitting activities. Following the war, ARRL announced the reactivation of the six major trunks it sponsored: three east / west lines and three north / south lines. Independent trunk lines also resumed operations.

But almost immediately, the trunk line concept resulted in dissatisfaction for many U.S. hams interested in traffic handling, and ARRL’s Communications Department became the recipient of an increasing level of complaints in the early post-war years. Two categories of complaint stood out:

- Large sections of the country were neither covered by nor reliably linked to the trunk lines. Consequently, amateur radio’s ability to pass traffic between different regions of the country was spotty and unreliable. Some of the complaints even came from trunk line managers themselves!

- The other oft-expressed concern was that the trunk line mode of operation led to over-reliance on a relatively small number of “iron-man” operators and better-equipped stations, leaving few, if any, opportunities for meaningful participation by those with lower power or less available time despite the fact that if one of the trunk line members went off the air for any reason a significant gap or “hole” in the trunk lines’ ability to move traffic smoothly quickly became evident. And some correspondents reported being turned away by trunk line managers when they attempted to volunteer!

The post-war ’40s

In late 1947 or early 1948, ARRL Communications Manager Ed Handy, W1BDI, formally tasked his Assistant CM, George Hart, W1NJM, with developing a League response to the limitations of the trunk lines. George’s involvement with the Wartime Emergency Radio System (WERS) during WWII arguably made him uniquely qualified among ARRL staffers to tackle this project.

Hart worked on the assignment throughout much of 1948, drawing on lessons learned from his WERS background and sifting through a potpourri of complaints and proffered remedies from traffic handlers and Section officials from coast to coast.

By the beginning of June 1949, W1NJM, working with other Communications Department staffers and melding suggestions from leading traffic handlers around the US, had arrived at a basic framework for the League’s proposed response to the shortcomings of the existing trunk line networks. He and Handy described the League’s plans with a July article mailed to all ARRL officials and appointees. At the same time, they were finalizing copy for the September 1949 issue of QST, wherein ARRL formally introduced members and other readers to its so-called “National Traffic Plan” (NTP).

The National Traffic Plan

To address concerns voiced by some of the trunk line leadership that ARRL intended to replace the trunk lines with the new system, Handy and Hart were in accord that the new offering from ARRL was intended to sit alongside the trunk lines. Indeed, since ARRL had no control over the independent lines, it was clear that the League did not have the power to discontinue trunk line operations by fiat. Nonetheless, Hart privately observed that he did not expect the trunk lines to survive in the longer term — after all, the shortcomings of the trunk line approach led to the creation of the new plan, not the reverse.

The new system concept was fairly simple and quite analogous to today’s “hub and spoke” system of commercial airline flights, wherein a traveler uses a sequence of car, bus or train, and regional airline (the “spoke”) to get to or from a major airport (“hub”) for a long-distance flight: Each evening, “local” nets — each typically encompassing an ARRL Section, U.S. state, or Canadian province — passed out-of-state traffic to a predetermined volunteer who collected that outbound traffic and then checked into a subsequent Region Net spanning as many as seven Section Nets. Similarly, representatives from Region Nets met to exchange inter-Region traffic in an Area Net. Then, as now, the first ten numbered Region Nets had their basis in FCC call areas, but exceptions existed, especially where an FCC call area straddled two time zones. Ultimately an Eleventh Region Net did not survive but a Twelfth Region Net consisted of the four “corner” states in the southwestern USA.

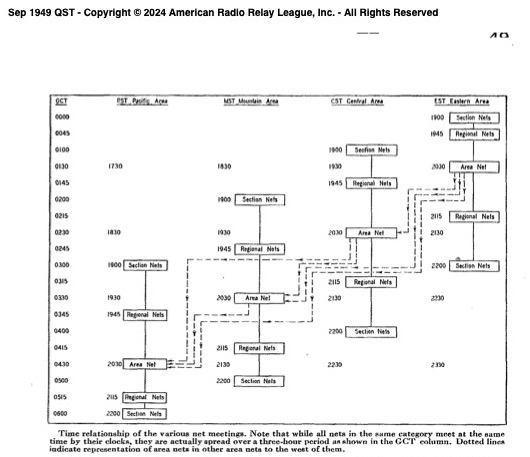

As originally announced, the NTP called for nets to officially operate at least five evenings a week — Monday through Friday — with each evening’s activities beginning with Section Nets throughout a given time zone meeting in parallel around 7 p.m. local time. Messages having a destination outside the originating Section were relayed during the Section Net session to a designated representative, who then checked into the associated Region Net at 7:45 p.m., where s/he exchanged messages with similarly tasked representatives from the other Sections in that Region. The representatives were to then bring the traffic so received back to the next session of their own Section Nets (generally, but not always, held later that same evening).

Messages with destinations beyond that Region were to be collected during the 7:45 p.m. Region Net by another volunteer (or “rep”) whose assignment was to bring them to the Area Net at 8:30 p.m. local standard time. (Some years later, HQ agreed with suggestions from the field to have the System schedule follow observed local time and switch back and forth with Daylight Saving Time changes.) Again, traffic staying within the Area was to be passed between the appropriate Region Net representatives during the Area Net session. Following the Area Net, “late” Region Net sessions would meet to distribute inbound traffic to representatives of the various Section Nets. Most, but not all, Section Nets then met — generally around 10 p.m. local time — to receive and distribute the incoming traffic to destination stations present in that net.

While the NTP in “full-up” mode called for all Sections to hold a “late” Section Net meeting at 10:00 p.m., Hart made it clear in the formal proposal to Handy that he understood population densities, levels of traffic-handling interest, and other local factors might make that an unattainable ideal. The proposal also indicated flexibility in allowing multiple contiguous Sections to come together in a single Section Net (such as the New York State Net) and in determining the exact coverage areas of the Region Nets, especially wherever a call area straddled two time zones.

As originally announced, the NTP had four Area Nets, corresponding to the four time zones covering the “lower 48” states. (Hawai`i and Alaska were still a decade away from attaining statehood.) In this plan, westbound traffic heading for a different Area was relayed by a designated representative from the originating Area Net to the destination Area Net. Thus, by the end of the evening, the Pacific Area Net might include as many as three direct check-ins from Eastern, Central, and Mountain Area Nets. If propagation or time constraints made it impossible for the designated inter-Area rep to meet the later Area Net, alternative routings — including the use of the trunk lines or out-of-net schedules — were encouraged to avoid delaying the relaying and ultimate delivery of traffic.

Eastbound traffic had to deal with the additional challenge posed by an evening-only sequence of origination and inter-Area relay: Delivery of eastbound out-of-Area traffic was guaranteed to require an extra calendar day. For eastbound traffic, the NTP called for out-of-net schedules agreed upon by the two stations involved in each specific schedule.

NTP Becomes NTS

Before 1949 ended, the “NTP” became “NTS” — the National Traffic System. Somewhat later, the ad hoc out-of-net schedules created to move traffic between Areas became formalized as the NTS Transcontinental Corps (TCC) — a group of volunteers whose free time, operating skills, and station capabilities allowed them to operate reliably across multiple time zones. Then as now, TCC assignments included a mix of out-of-net schedules and direct check-in to destination Area, Region, and Section nets, as appropriate.

TCC improved upon the trunk line concept in at least four important ways:

- TCC operators from anywhere in their Area could perform any TCC function for their Area.

- TCC operators could participate only one day a week if they so chose.

- TCC operators were empowered to move traffic between the Areas through a structured set of schedules between counterpart operators in two different Areas or with direct check-in to another Area Net if propagation supported it.

- To speed up the relaying and delivery of eastbound messages, TCC operators were also empowered to check directly into destination Region and Section nets, as necessary, and were to be given priority by the net control station because they might have traffic headed for multiple nets that were meeting concurrently.

From the very beginning, NTS’s greatest strengths as compared to the trunk lines were these:

- NTS relied on “representatives” and a logically structured system of tiered nets that, taken together, eliminated the need for the “iron-man” traffic handler and made it unnecessary for traffic handlers to know where specific relay stations were located.

- NTS could move radiograms originating in any community in the country to virtually any other community through the rigorous coupling of the long-haul levels of the NTS to the Section-level nets that the structure called for in all U.S. and Canadian Sections.

- Only in the destination (Section-level) nets did the net control station need to have a good grasp of the local geography and the locations of the net members, and only in those Section Nets (and later the VHF Local Nets) was iron-man participation useful. As a result, an individual amateur could perform a valuable contribution within NTS by serving as a representative at any of three different levels of the System with no greater time commitment than just one night a week if she or he so desired.

Ultimately, a far, far greater number of interested amateurs could — and

did — participate meaningfully in NTS than in the trunk lines that existed in 1949.

Of course, many states or ARRL Sections already had nets that were essentially tailor-made for the role of Section Net within the NTS structure; in virtually all instances, these nets quickly became part of the new System without changing a thing beyond identifying a representative to the Region Net each evening. For the typical traffic handler in an ARRL Section Net, NTS brought only advantages: a systematic umbrella for freeing Section Net participants from having to worry about routings to get out-of-Section messages to their specific destinations, along with far more opportunity for growth “up the ladder” and participation in long-haul messaging than the trunk lines had ever provided.

Despite its obvious advantages, the start-up of the fledgling National Traffic System in the fall of 1949 and its operations for the next few years came with considerable birthing pains. In addition to resistance from some long-established trunk line participants, ionospheric propagation during the sunspot minimum of the early 50s brought long skip to 80 meters many winter evenings when the maximum usable frequency (MUF) dropped below 3.5 MHz. EAN Manager George Sleeper, W2CLL (SK), wrote on the back of one of his monthly reports to HQ that in all his years of hamming he had never experienced 80-meter winter propagation as bad as that of 1951.

Another start-up problem for NTS was a direct consequence of most states’ and provinces’ relatively light population density in the Mountain time zone. There, the planned Region and Area Net structure got off to a rocky (dare we say “Rocky”?) start and was soon abandoned because it was largely unstaffable. Instead, as geographically appropriate, Section and Region Nets in the Mountain Area became part of either the Pacific Area or the Central Area.

In November of 1954, the Eastern Area began regular Saturday operations, and by 1958, ARRL’s Communications Manager (still Ed Handy, W1BDI) reported to the Board of Directors that NTS was officially operating 365 days a year.

Participation in NTS grew throughout the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, and high enrollment levels coupled with refinements to net procedures led to System-wide increases in total messages passed and traffic net efficiencies, peaking in the late ’70s and early ’80s. For instance, the Eastern Area Net — which met on 80-meter CW for one hour or less every evening at 8:30 Eastern Time — cleared more than 300 messages in that hour at least a dozen times in the late 70s!

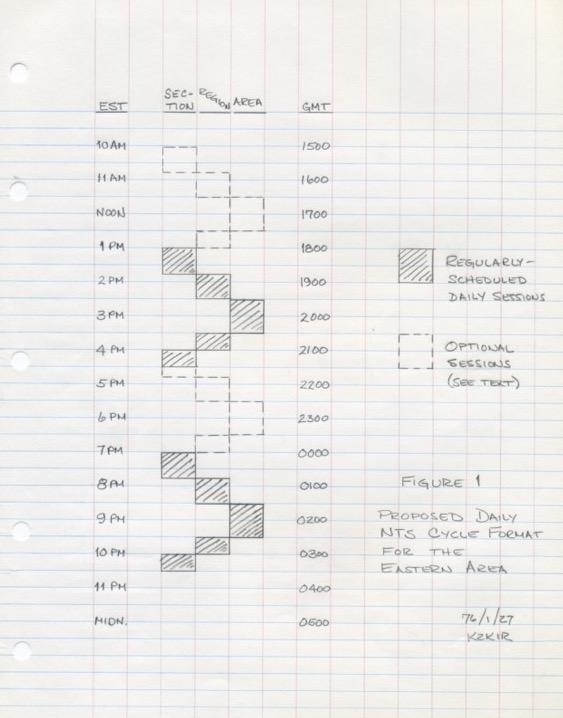

But although virtually all Region and Area net sessions met on CW in the evening during the early years, the number of amateurs at home during the day was increasing through the ’60s and ’70s — so much so that a parallel daytime sequence of Section / Region / Area / TCC functions — using predominantly SSB — was officially added to the NTS structure in the mid-’70s. One great benefit of this System expansion was that TCC operators could now bring eastbound traffic to nets in the Central and Eastern time zones earlier in the day, thus substantially increasing the likelihood of “same day delivery” for afternoon originations and “next day delivery” — often in less than 24 hours — for evening originations out west despite those messages having to travel “against” the sun.

Using terminology from a “full up” 4-cycle System schedule adopted in 1976 for periods of high traffic volumes — especially the annual Simulated Emergency Test week and Thanksgiving to Christmas holiday period, as well as unpredictable high-impact natural disasters — the new daytime sessions were predominantly “Cycle 2” sessions while the original evening net meetings and TCC skeds became “Cycle 4” — terminology still in use today.

Later still, with the advent of personal computers, came interest in digital message handling. Ultimately, this became formalized as NTS-D, even though that structure resembles the old trunk lines more than the traditional modes that form the bulk of Cycles 2 and 4.

This period also saw an increase in local nets forming — especially on VHF, where many Technician class licensees were delighted to get involved in structured traffic handling and net operations. Many of these new nets developed formal affiliations and representation with their Section Nets, and the “Local Net” officially became a part of NTS. Unfortunately, during the same period, policy within the League field organization changed: The Section Traffic Manager (STM) appointment became optional; consequently, the promotion of standardized message handling and traffic net procedures has sometimes been neglected where it is needed most and — since Section and Local Nets in NTS are the purview of the local SM and his/her STM — promotion of, and coverage by, NTS continues to vary throughout the United States.

Area Staffs

As NTS matured, ARRL HQ formalized the role of Area Staffs consisting of all Region and Area Net managers and TCC directors within each of the three Areas. These Staffs typically:

- recommended candidates for vacant net manager or TCC director positions in their respective areas, each such appointment to be approved or rejected by the League’s Communications Manager;

- deliberated issues and opportunities confronting their Area of the System;

- recommended system improvements and other changes for consideration by the other two Area Staffs and ARRL HQ.

To incorporate viewpoints from Section and Local level nets and other active traffic handlers, all three Staffs added multiple “members at large” to their rosters over time.

Canada and other countries

For the first four decades of NTS existence, Canadian traffic handlers were full participants in the System. Their east coast Section nets fed the Thirteenth Region Net (later called the Eastern Canada Net), which was a full member of NTS’s Eastern Area, while their western Section nets were part of the 7th and 10th Region Nets (RN7 and TEN, respectively). But in 1988, Canada’s longstanding national amateur radio organization withdrew from its role as the Canadian Division of ARRL and in 1993 merged with another Canadian organization to become the Radio Amateurs of Canada. One side effect of these changes was to officially eliminate the Canadian portion of the then-existing NTS structure. In subsequent years, many Canadian traffic handlers have unofficially returned by checking into NTS Region or Section Nets contiguous to the Canada / USA border. One example: At various times, Ontario traffic handlers have checked into NYS (a Section Net) and, at other times, have held representation and net control assignments in 2RN.

As historical prohibitions on international traffic by radio amateurs in other nations benefited from eased government and telecommunications authority restrictions, NTS nets increasingly were called upon to forward 3rd-party messages to and from those countries. In response, a new “Region” was added to the Eastern Area, and representation to and from IATN — the International Amateur Traffic Net — became a reality. Regrettably, the infrequent occurrence of international traffic did not bode well for the long-term success of daily IATN representation although dedicated representatives attempted to keep the linkage active for some years. More recently, Caribbean traffic has been passed via a gateway amateur in Puerto Rico (which itself is a part of 4RN). Other international locations are handled via digital and CW links with gateway operators in Germany.